FATHER TAB TURNS 100

Saturday, January 7, 2006

Father of LSD nears the century mark

Scientist calls drug 'medicine for the soul'

By CRAIG SMITH

THE NEW YORK TIMES

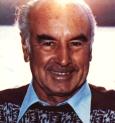

BURG, Switzerland -- Albert Hofmann, the father of LSD, walked slowly across the small corner office of his modernist home on a grassy Alpine hilltop here, hoping to show a visitor the vista that sweeps before him on clear days. But outside there was only a white blanket of fog. He picked up a photograph of the view on his desk instead, left there perhaps to convince visitors of what really lies beyond the window.

Hofmann will turn 100 on Wednesday, a milestone to be marked by a symposium in Basel on the chemical compound that he discovered and which unlocked the Blakean doors of perception, altering consciousnesses around the world.

As his time left grows short, Hofmann's conversation turns ever more insistently around one theme: man's oneness with nature and the dangers of an increasing inattention to that fact.

"It's very, very dangerous to lose contact with living nature," he said. "In the big cities, there are people who have never seen living nature, all things are products of humans," he said. "The bigger the town, the less they see and understand nature."

And, yes, LSD, which he calls his "problem child," could help reconnect people to the universe.

Rounding a century, Hoffman is physically reduced but mentally clear. He ambles with pleasure through memories of his boyhood, but his bright eyes flash with the recollection of a mystical experience he had on a forest path more than 90 years ago in the hills above Baden, Switzerland.

The experience left him longing for a similar glimpse of what he calls "a miraculous, powerful, unfathomable reality," but it also left him deeply connected to nature and helped shape his future.

"I was completely astonished by the beauty of nature," he said, laying a slightly gnarled finger alongside his nose with the recollection, his longish white hair swept back from his temples and the crown of his head. He became particularly fascinated by the plant kingdom, by the mechanisms through which plants turn sunlight into the building blocks for our own bodies. "Everything comes from the sun via the plant kingdom," he said.

Hoffman went on to study chemistry and took a job with the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz Laboratories because the company had started a program to identify and synthesize the active compounds of medically important plants. He soon began work on the poisonous ergot fungus that grows in grains of rye.

Midwives had used the deadly material for centuries to precipitate childbirths, but chemists had never succeeded in isolating the chemical that produced the pharmacological effect. Finally, chemists in the United States identified the active component as lysergic acid, and Hofmann began combining other molecules with the unstable chemical in search of pharmacologically useful compounds.

Hofmann's work produced several important drugs, including a compound to prevent hemorrhaging after childbirth that is still widely used around the world today. But it was the 25th compound that he synthesized, lysergic acid diethylamide, that was to have the greatest impact.

As he was synthesizing the drug one Friday in April 1943, he recalled, he first experienced the altered state of consciousness for which it became famous. He rode his bicycle home, lay down and spent hours mesmerized by hallucinations.

"Immediately, I recognized it as the same experience I had had as a child," he said. "I didn't know what caused it, but I knew that it was important."

When he returned to his lab the next Monday, he tried to identify the source of his strange experience. He realized he must have somehow ingested a trace of LSD.

"LSD spoke to me," Hofmann said with an amused, animated smile. "He came to me and said, 'You must find me.' He told me, 'Don't give me to the pharmacologist, he won't find anything.' "

He first experimented with the drug, taking a dose so small that even the most active toxin known at that time would have had little or no effect. The result was a powerful LSD experience.

He later participated in clinical tests in a Sandoz laboratory but found the experience frightening and realized that the drug should be used only under carefully controlled circumstances.

Later, he wrote to the German novelist Ernst Junger, who had experimented with mescaline, and proposed that the two take the new compound together. In 1951, together with a medical doctor, the two men each took 0.05 milligrams of pure LSD at Hofmann's home accompanied by a vase of roses, music by Mozart and a burning stick of Japanese incense.

"That was the first planned psychedelic test," Hofmann said. He took the drug dozens of times after that, he said, and only once experienced a bad trip. Now his hallucinogenic days are long behind him.

"I know LSD; I don't need to take it anymore," he said.

He calls LSD "medicine for the soul" and is frustrated by the worldwide prohibition that has pushed it underground. "It was used very successfully for 10 years in psychoanalysis."

But the drug was hijacked by the youth movement of the 1960s and then unfairly demonized, he said. He concedes LSD can be dangerous and calls its promotion by Timothy Leary and others "a crime."

"It should be a controlled substance with the same status as morphine," he said.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home